31 March 2021

Over the past decade, food price inflation hasn’t been an issue that troubled the financial markets; however, we believe that could change soon.

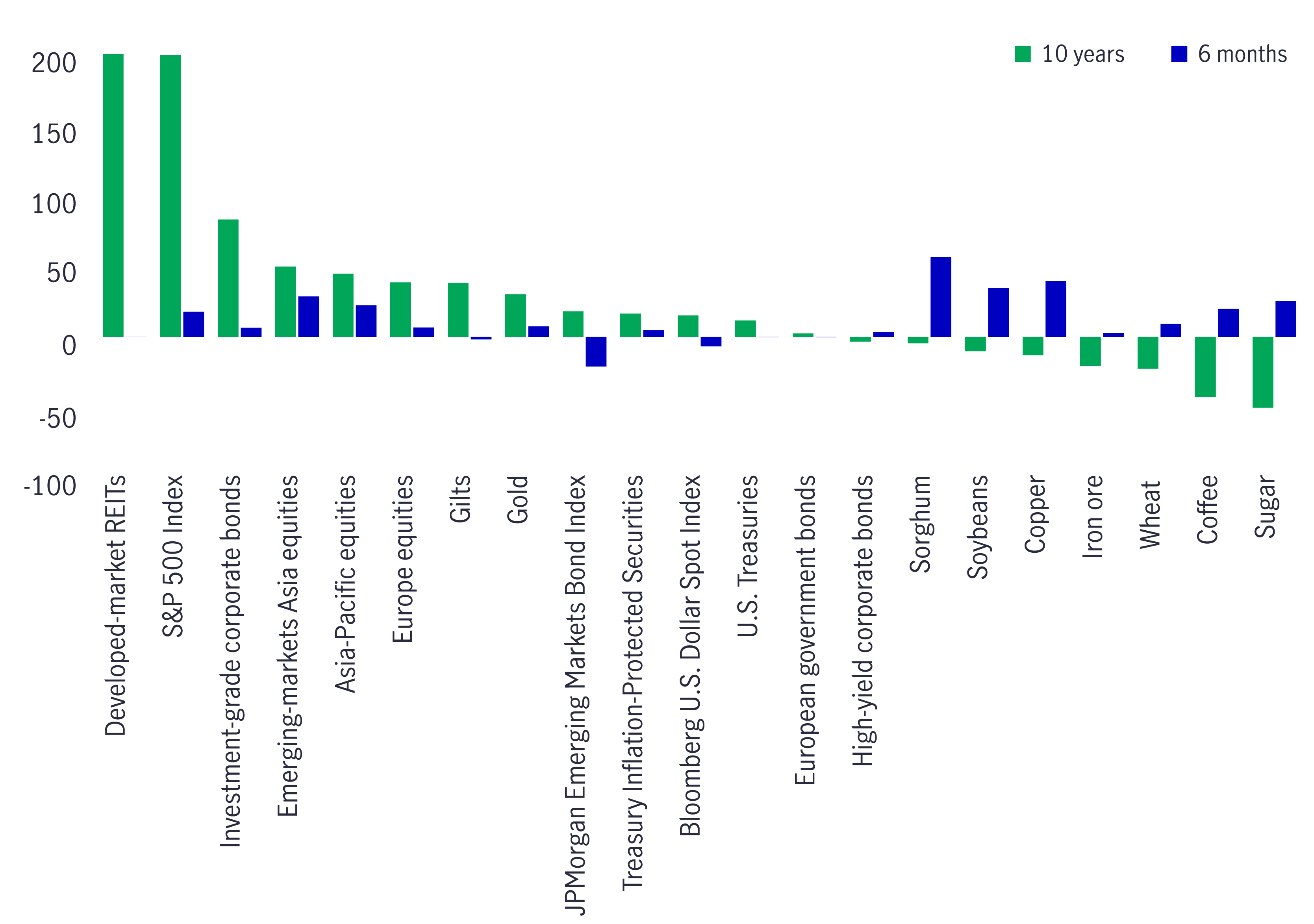

Food prices have trended significantly lower over the past decade for many reasons and have, to a large extent, underperformed other commodities and asset classes. While the last half of 2020 saw a rise in food prices, long-term forecasts from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development suggest real food prices will likely remain at or below current levels for the next 10 years.¹ We have a slightly different view—we think consensus is underpricing the risk of a further sharp increase in food prices.

Having underperformed for 10 years, food price inflation is making a comeback (%)

Source: Bloomberg, Manulife Investment Management, as of 4 December, 2020. Green bars represent cumulative 10-year returns for various asset classes. Blue bars represent cumulative 6-month returns for soft commodities (food items).

Food price inflation typically affects the lower-income group most since food purchases account for a bigger portion of their household income. Therefore, a sharp, unexpected rise in food price inflation could widen the income gap between the haves and have-nots, exacerbating a situation that has already been made worse by the COVID-19 outbreak.

While policies put in place to contain the economic damage brought about by the pandemic have so far helped to prevent a financial crisis, it’s important to recognize that quantitative easing—a key component of the global response—has worsened income inequality through asset price inflation. In our view, a protracted period of food price inflation, when combined with other forms of bad inflation, will weigh on aggregate demand, denting global growth prospects.

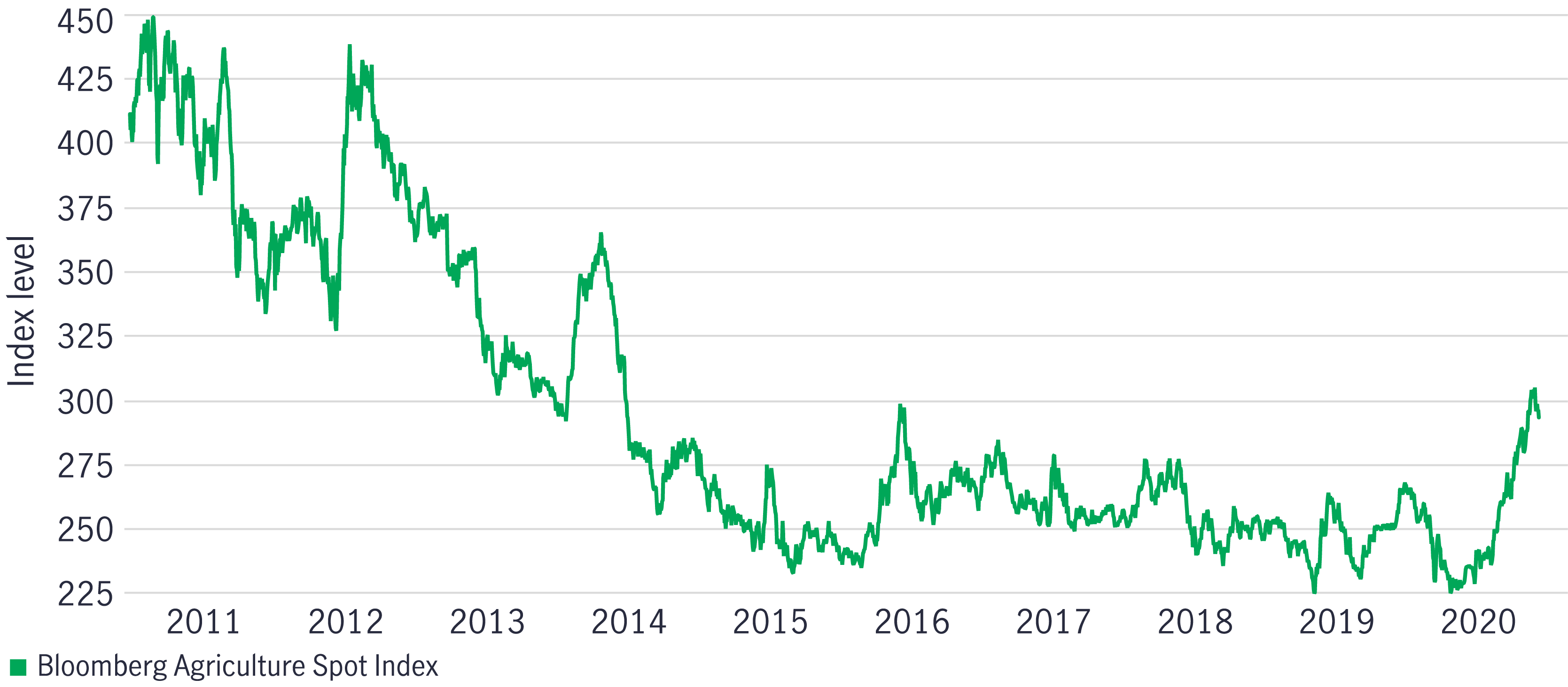

Commodity prices rising since April 2020

Source: Macrobond, Manulife Investment Management, as of 4 December, 2020.

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered a surge in Consumer Price Index (CPI)-measured food price inflation, driven by an increase in demand for groceries and the shift from dining at restaurants and schools to eating at home. Governments have also built up strategic food stockpiles to insulate their economies from further supply disruptions. On the supply side, the pandemic has shuttered food processing plants and disrupted global trade. Extreme weather events—from droughts in the United States, Russia, and Brazil to flooding in China, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia—have also negatively affected harvests and supply chains around the world, sending crop prices higher. The Bloomberg Agriculture Spot Index, a gauge of nine crop prices, has risen by roughly 30% since late April to highs not seen in nearly four years, reversing a near decade-long downtrend in global food prices.²

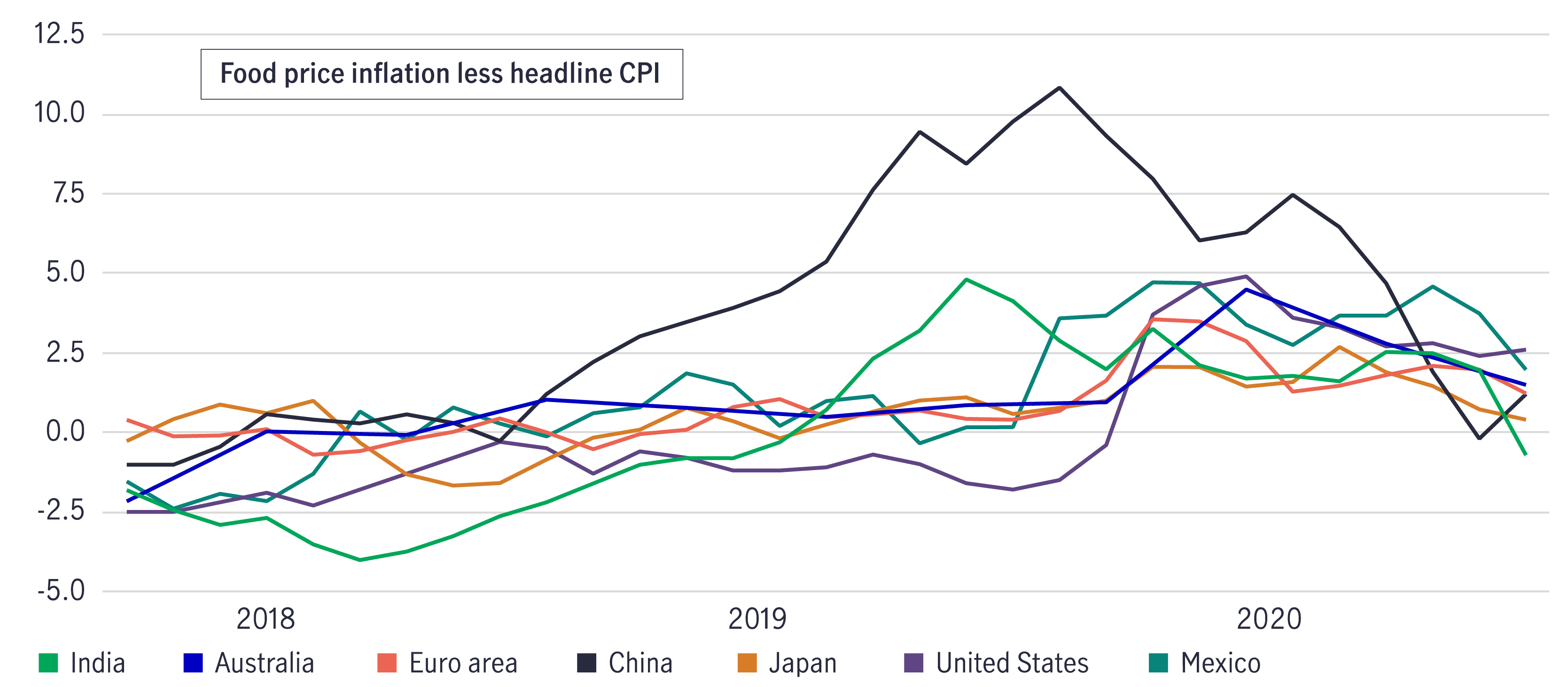

Food price inflation has consistently outpaced headline inflation in the past year (%)

Source: Macrobond, Manulife Investment Management, as of 30 December, 2020.

That said, it’s important to note that food price inflation was already trending higher before the pandemic. A quick analysis of food price inflation (relative to the CPI) in a broad range of economies confirms this. For instance, CPI food inflation in Mexico has risen to 4.6 percentage points above headline CPI inflation. In Q3 2018, CPI food inflation was 2.4 percentage points below headline CPI inflation.²

The rise in food price inflation isn’t only COVID-19 related—structural drivers also play a key role in determining price levels.

Rising population and income growth in emerging markets have led to an increase in appetite for more protein in these economies. Unsurprisingly, the income elasticity of protein demand is much higher for poorer households than richer ones. Demand for protein among households in developed markets has also risen as a result of the growing popularity of plant-based diets on the back of rising concerns over environmental protection and obesity.

Many factors have contributed to keeping a lid on food supply. The multi-year decline in food prices has disincentivized new agricultural investments to the extent that growth in agricultural supply hasn’t kept up with demand; water supply and arable land have decreased (the former due to global warming and the latter due to erosion, pollution, and over farming), limiting growth in global food production; urbanization and industrialization—particularly in emerging markets—have created a new source of competition for land needed for agriculture; and, finally, the frequency of extreme weather events such as plagues, floods, and bushfires have increased alongside climate change concerns, which is negative for harvesting.

Research from the United Nations World Food Programme shows that the number of people facing acute food insecurity could have doubled to nearly 265 million last year—an outcome of the COVID-19 outbreak.³ Meanwhile, Oxfam forecasts that 12,000 people die from hunger every day as a result of the pandemic.⁴

Indeed, food security was already an issue pre-COVID-19 and, as with many other issues, the pandemic has simply exposed that vulnerability. Food security isn’t just a problem for poor economies, it’s also a growing issue in rich countries. For instance, in the United States, nearly 28 million adults—13% of all adults in the country—reported that their household sometimes or often didn’t have enough to eat.⁵ Meanwhile, food bank lines have grown longer during the pandemic and school closures have also meant that some children who depended on schools for a daily meal have gone hungry.

The United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization highlights four key pillars of food security:

Income and class inequality directly affect access to food produced. Indian economist Amartya Sen, who won the Nobel Prize in 1998 for his work in welfare economics, argued that famine wasn’t caused by a lack of availability, but because people didn’t have the money and, importantly, the power to access food that had been produced.⁶ Africa is a good example: Since 2000, hunger in Africa—proxied by the prevalence of undernourishment—has increased by 25.8% despite the fact that food production has simultaneously increased by 8.6% per person.⁷

Inequality isn’t a new issue, but it has gotten worse in the last decade, amplified by a few developments:

To objectively gauge which economies could be most vulnerable to food inflation, we calculated z-scores⁸ for 31 economies/regions—which we follow regularly and believe to be a good representation of the global economy— based on multi-year averages of the following variables that, in our view, are good indicators of exposure to food price volatility:

By calculating a composite Z-score from each of these variables, we find that of the 31 major economies/regions we tracked, the most vulnerable to higher food prices (highest Z-scores) are the Philippines, India, Indonesia, Vietnam, and China. The least vulnerable to higher food prices (lowest Z-scores) are Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Norway, and the United States.

Z-scores—which economies are most exposed to food price inflation?

Source: World Bank, EIU's 2018 Global Food Security Index, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Manulife Investment Management, as of December 2019. The results shown are based on Z-score calculations of 31 economies that provide a comprehensive view of the global economy. Z-scores are calculated based on multiple-year averages of prevalence of undernourishment; net food exports as a percentage share of GDP; agricultural water withdrawal as a percentage share of total renewable water resources; total internal renewable water resources per capital, arable land (hectares per person); GDP per capital; and food consumption as a percentage share of household expenditure.

While food prices may not appear as relevant to global markets as U.S. Federal Reserve decisions or the announcement of large fiscal packages, it’s important to remember that a food and/or water crisis represents a sizable investment risk with far-reaching economic, social, and geopolitical implications.

In our view, markets have underappreciated the risks associated with food price inflation and the widening income gap—calls to address chronic hunger through a necessary structural reform of economy and institutions, including the redistribution of wealth and power, are likely to grow louder. As these issues come to the fore, we could see heightened political risk, particularly in key areas of the world where hunger, exacerbated by the COVID-19 shock, is evident.

1 Organisation for Economic Development and Co-operation, December 2020.

2 Macrobond, as of 4 December, 2020.

3 United Nations World Food Programme, 21 April, 2020.

4 “12,000 people per day could die from Covid-19 linked hunger by end of year, potentially more than the disease, Oxfam warns,” Oxfam, 9 July, 2020.

5 “Tracking the COVID-19 Recession’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 15 January, 2021.

6 Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation, Amartya Sen, 1981.

7 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 30 November, 2020.

8 A Z-score describes the position of a value in terms of its distance from the mean (average). It is measured in terms of standard deviations from the mean.

Latest asset allocation views amid latest Middle East developments

Against a backdrop of elevated uncertainty, the Multi Asset Strategy Team (MAST) summarizes key market moves, and the potential cross-asset implications.

Middle East developments - Implications for Asian equities and fixed income

The Asian Equities and Asian Fixed Income team assess the recent Middle East developments and implications for Asia asset classes.

Middle East Conflict and Market Risk

Alex Grassino, Global Chief Economist, shares his latest views on the recent increase in military activity and geopolitical tensions in the Middle East.

Latest asset allocation views amid latest Middle East developments

Against a backdrop of elevated uncertainty, the Multi Asset Strategy Team (MAST) summarizes key market moves, and the potential cross-asset implications.

Middle East developments - Implications for Asian equities and fixed income

The Asian Equities and Asian Fixed Income team assess the recent Middle East developments and implications for Asia asset classes.

Middle East Conflict and Market Risk

Alex Grassino, Global Chief Economist, shares his latest views on the recent increase in military activity and geopolitical tensions in the Middle East.