15 April 2022

Fiona Cheung, Head of Global Emerging Markets Fixed Income Research

Joseph Huang, Head of Fixed Income Research, South Asia

On 12 April, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka announced that it would suspend payments on US $51 billion in offshore debt obligations to preserve the nation’s dwindling foreign reserves1. The statement indicated that technical default was imminent2. In this investment note, Fiona Cheung, Head of Global Emerging Markets Fixed Income Research, and Joseph Huang, Head of Fixed Income Research, South Asia, explain the difficult road ahead for Sri Lanka amid default and restructuring, as well as the unique lessons this incident offers investors for adopting holistic credit frameworks to assess sovereign high-yield credits.

Sri Lanka’s central bank announcement did not come as a surprise to investors. Indeed, the country’s economic condition has progressively deteriorated over the past two years. After recently experiencing massive food and fuel shortages, the government declared a state of emergency on 1 April due to surging public protests, only to later rescind the order as they swelled further. As foreign exchange reserves dwindled, the government ultimately decided to suspend all payments to foreign debtors until a formal restructuring could be negotiated, thereby averting a potential humanitarian crisis.

We believe that sovereign defaults do not occur in a vacuum, but are the product of a country’s economic structure, policy decisions, and external macro shocks that accrue over time. In particular, balance-of-payment crises are nothing new in Sri Lanka: since 1965, the country has received 16 loans from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). As an island nation that relies on hard currency from exports and services to purchase critical goods, foreign exchange reserves have always been a vital metric for credit investors.

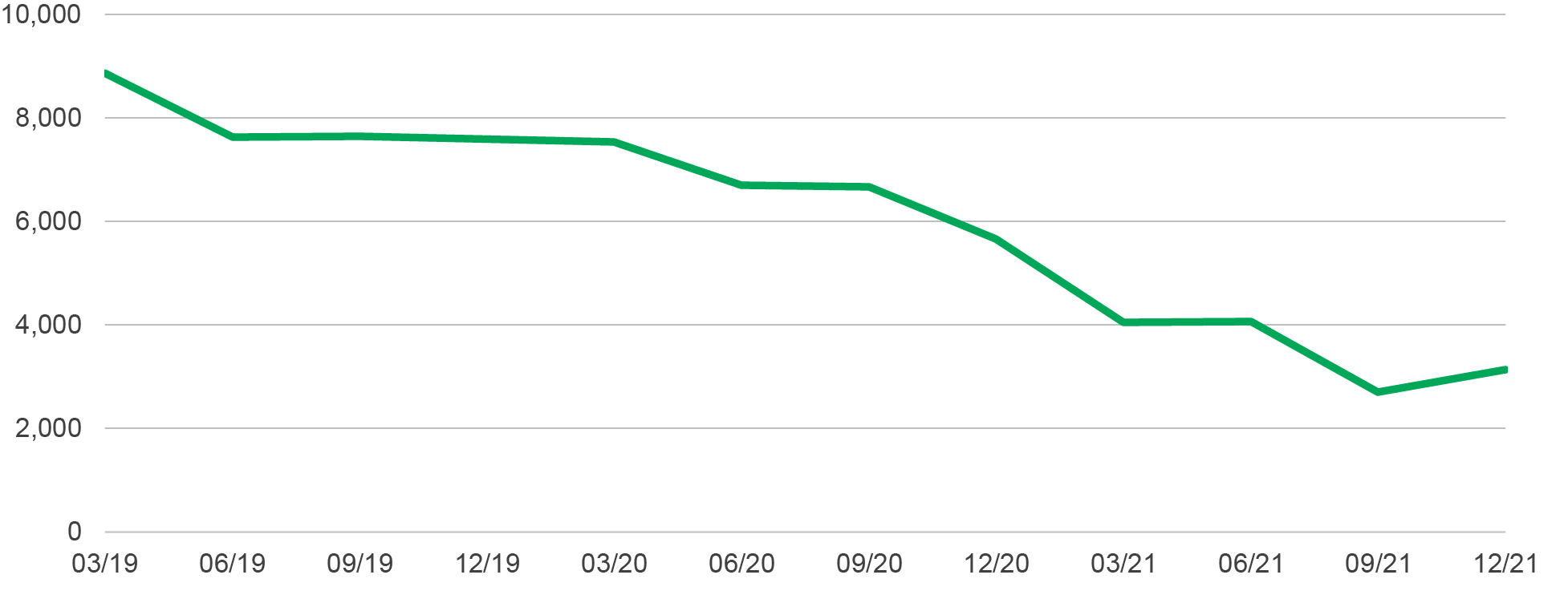

Over the past two years, the country has faced a raft of unanticipated challenges that exacerbated this historical financial vulnerability. Capital inflows suffered due to COVID-19 travel restrictions that crippled the economically important tourism sector. International tourists’ arrivals fell by 61.7% in 2020. Additionally, the government banned fertiliser imports in April 2021, an unexpected decision that reduced productivity and revenues in the tea and rubber industries – two of the nation’s key exports. As a result, foreign exchange reserves progressively decreased to dangerously low levels (see Chart 1).

Chart 1: Sri Lanka’s dwindling foreign exchange reserves (US dollars, millions)3

Although the economy showed signs of potential recovery in the first quarter of 2022, the rise of global inflation, particularly in energy and food, coupled with the Russia-Ukraine conflict (these two countries accounted for a significant number of tourists), posed new challenges. Ultimately, a widening dual deficit (current account and fiscal) and depreciating rupee forced the government to decide how its limited resources would be used.

The imminent default of Sri Lanka provides a unique case study for investors to understand how fundamental credit analysis can intersect with ESG factors to produce a more robust assessment of a country’s creditworthiness.

Indeed, while traditional credit metrics showed the country’s potential vulnerability to a balance of payments of crisis, as early as 2018 we identified other ESG-related factors that investors could consider to enrich the analysis.

Looking forward, we envisage a long, difficult road ahead for Sri Lanka. Indeed, default is just the beginning of an extended process required to address the underlying problems, as well as negotiate with a disparate group of offshore bond holders.

The first order of business is to restore political order in a country that faces a humanitarian crisis and has not experienced stability for several years. Protestors are calling for the resignation of Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa, whose cabinet quit en masse in early April. He has indicated that he will not step down.

A complete political reset in this environment may not be possible. Still, a caretaker government may be a necessary first step to regain the people’s trust, as well as key international financial stakeholders for significant lending packages. Although the previous constitutional crisis took around two months to resolve, we believe it could take much longer this time around due to the severity of the crisis, the scope of the changes needed, and the limited options available.

We think once a stable political environment is achieved, the real work can begin.

Finally, we think that the restructuring process will be long and arduous, given the aforementioned obstacles. Investors may look to other emerging market examples such as Lebanon and Ecuador, as potential templates (with some differences) for how the pace of negotiations may proceed and the level of haircuts ultimately required. We believe bondholders of Sri Lanka debt are likely to face a bond face value haircut in the 20-50% range plus distress exchanges into new bonds with reduction in coupon rate and the extension of bond tenors up to 15 years or so.

Governance risks exist in every credit market, whether they are developed or emerging. However, the nature of governance risks and how they should be assessed differ significantly between these two types of markets. In Asia, we believe that a more holistic credit assessment framework, integrating both quantitative and qualitative factors, is integral in fully understanding the risks.

Besides Sri Lanka, high-profile default should remain fresh in the memory of other Asian US dollar/high-yield investors over the past year. Indeed, markets can be too complacent with the custom belief that potential bailouts and recovery would be in place without testing that assumption. Thus, qualitative factors in assessing Asian sovereign or corporate credits are imperative. We believe that a more holistic credit assessment framework, integrating both quantitative and qualitative factors, is critical as there should be no room for any benefit of doubt when assessing Asian credits.

1 Central Bank of Sri Lanka, as of 13 April 2022.

2 Rating agency Fitch Ratings is reported to view Sri Lanka’s foreign debts on a default process. Although the central bank has stated that payments on the USD-bonds will not be made, default will only technically occur when bond-coupon payments are missed on 18 April and the passage of 15-30 days.

3 Central Bank of Sri Lanka, as of 13 April 2022.

4 The IMF is likely to provide initial, smaller support to avert a humanitarian crisis. However, a more substantial package, including debt restructuring and relief, will likely only be established under a more stable political environment.

Latest asset allocation views amid latest Middle East developments

Against a backdrop of elevated uncertainty, the Multi Asset Strategy Team (MAST) summarizes key market moves, and the potential cross-asset implications.

Middle East developments - Implications for Asian equities and fixed income

The Asian Equities and Asian Fixed Income team assess the recent Middle East developments and implications for Asia asset classes.

Middle East Conflict and Market Risk

Alex Grassino, Global Chief Economist, shares his latest views on the recent increase in military activity and geopolitical tensions in the Middle East.

Latest asset allocation views amid latest Middle East developments

Against a backdrop of elevated uncertainty, the Multi Asset Strategy Team (MAST) summarizes key market moves, and the potential cross-asset implications.

Middle East developments - Implications for Asian equities and fixed income

The Asian Equities and Asian Fixed Income team assess the recent Middle East developments and implications for Asia asset classes.

Middle East Conflict and Market Risk

Alex Grassino, Global Chief Economist, shares his latest views on the recent increase in military activity and geopolitical tensions in the Middle East.