5 October, 2020

Rana Gupta, Indian Equities Specialists

India has not been spared from the global damage caused by COVID-19 pandemic, with the country’s lockdown contributing to a precipitous drop-in economic activity. However, we believe that the worst is likely behind us, as growth is bottoming out, government policies remain supportive, and virus-related health metrics are stabilising. In this investment note, Rana Gupta and Koushik Pal, Indian Equities Specialists, explain that despite the setback, India should benefit from a path of economic normalisation in the short-term and an acceleration of existing structural drivers, such as formalisation and government reinvestment, over a longer time frame.

Our consistent view on India, even before the COVID-19 outbreak, was that the economy faced a cyclical downturn driven by deceleration in the informal economy and credit slowdown among the non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) due to tighter monetary conditions.

While we had expected an economic recovery in the first half of 2020 on the back of policy support from the "Three R's"1, the pandemic and subsequent government lockdown stifled any upturn. Consequently, second-quarter GDP fell by approximately 24% year-on-year.

Despite this sharp dip in growth, GDP is a backwards-looking number, reflecting the damage of the strict lockdown implemented in India until June. Since then, the economy has gradually reopened, and many activities are normalising. In our view, the worst is likely behind us for three reasons:

These factors augur well for an ongoing rebound in activity and sequential improvement in economic data after the disruption experienced since March. While the upcoming recovery is expected to be uneven, we remain positive on India’s medium-term growth potential, given formalisation should continue to boost the digital economy, and the government's reinvest policies that should herald a revival in manufacturing.

Middle East developments - Implications for Asian equities and fixed income

The Asian Equities and Asian Fixed Income team assess the recent Middle East developments and implications for Asia asset classes.

Quick comments on geopolitical tensions in the Middle East

Alex Grassino, Global Chief Economist, shares his latest views on the recent increase in military activity and geopolitical tensions in the Middle East.

Economic and market implications for oil prices

Recent geopolitical tensions involving Iran have renewed focus on oil prices and their potential economic and market effects. Paul Kalogirou, Head of Client Portfolio Management, Asia & Global Multi-Asset Solutions, shares latest views on it.

We believe that GDP growth has bottomed out, and we should see sequential improvements going forward – in the fiscal year 20222, we expect double-digit growth in real GDP. However, the recovery will remain uneven across sectors and geographies. That said, with most urban centres now operating almost normally, our confidence in a resumption of activity has subsequently increased.

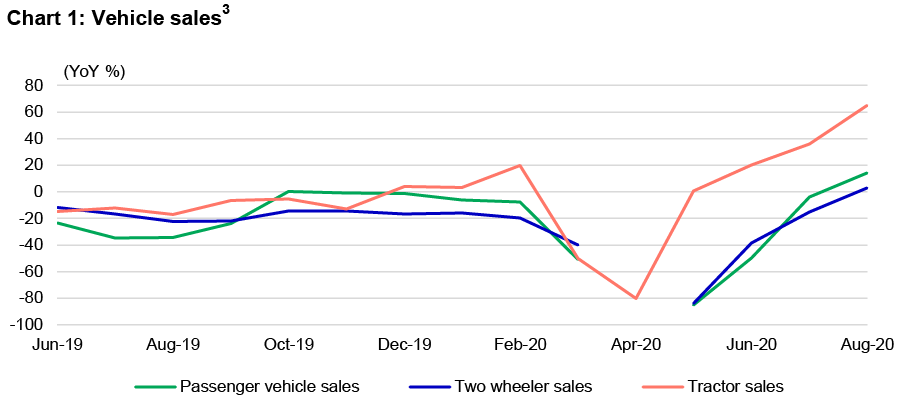

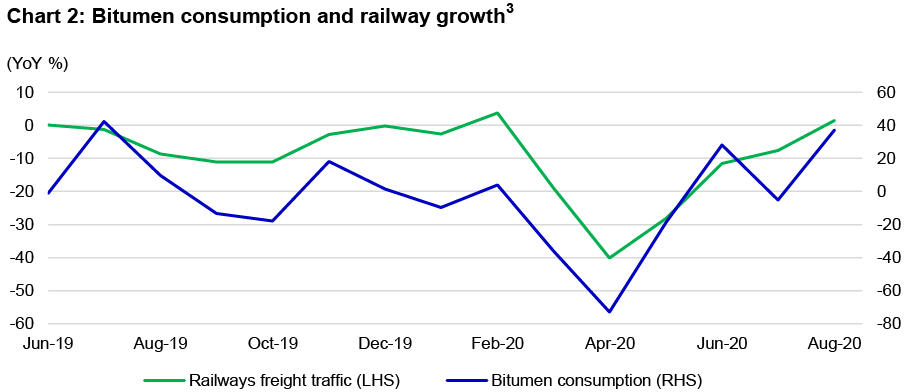

Many bottom-up indicators on the demand-and-supply side provide evidence for this thesis. Vehicle sales across all categories have improved (See Chart 1). In addition, a rise in bitumen consumption points to a pick-up in the construction sector, while positive rail-freight growth signifies that industrial activity has also started to normalise, albeit gradually (See Chart 2).

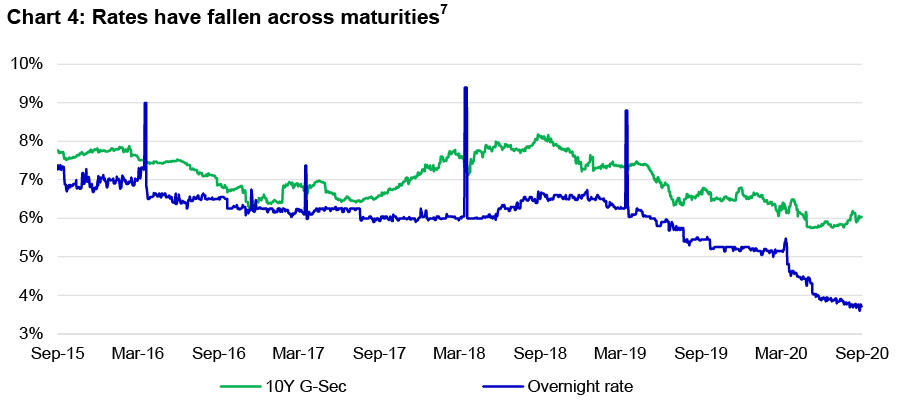

Divergence in monetary conditions is the critical difference between the earlier cyclical slowdown and the post-pandemic recovery phase. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has aggressively cut rates by 115 basis points (bps) since March 2020. It has also provided the banks with additional LTRO and TLTRO liquidity (roughly 4.5% of GDP) at this lower policy rate and continued to intervene in the bond market to ensure that it functions smoothly4.

Domestic monetary conditions have also improved, as India's external account situation remains favourable: the capital and current accounts are in better health, with the country's balance of payments in surplus. From a current account perspective, this is primarily due to a rising share of net exports in electronics and chemicals, as well as falling crude oil prices. Robust inflows are driving the capital account recovery in foreign direct investment and foreign portfolio participation in India’s digital economy and manufacturing revival. As a result, India's foreign-exchange reserves increased from US$457 billion in December 2019 to US$541 billion by the end of August 20205.

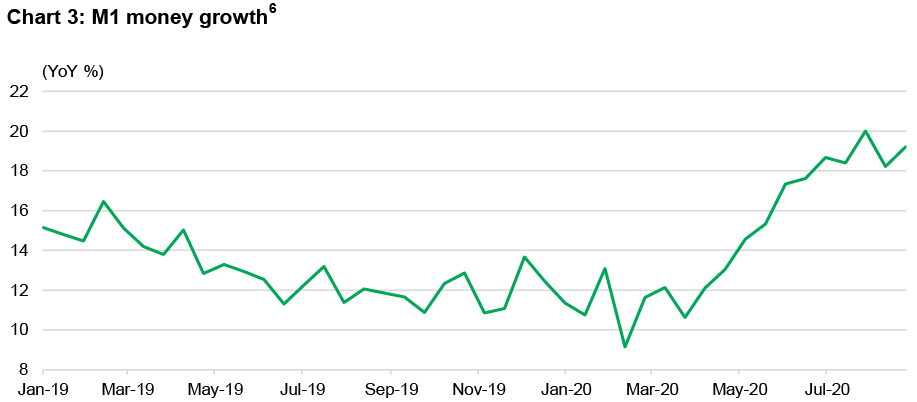

Benign liquidity conditions are reflected in money- supply (M1) growth (See Chart 3) and lower rates on both the short and long end of the curve (See Chart 4). In fact, real rates are now in negative territory for the first time in five years.

While we expect credit costs to rise from these levels, they will not be debilitating for the banking sector due to lower rates and ample liquidity. An active and vigilant RBI is likely to prevent any systemic refinancing issues. Most major private banks have also raised capital recently, and their balance sheets are adequately capitalised.

Overall, we expect the credit-transmission mechanism to pick up. This will be driven by a gradual reopening of the economy, the containment of asset-quality deterioration, and the well-capitalised balance sheets of the large private-sector banks. There are also lower nominal rates and negative real rates.

Finally, we do not anticipate any substantial depreciation in the value of the rupee, as better capital flows will help to revive growth. In addition, we do not believe that the trade deficit will expand meaningfully, as the share of domestic manufacturing has improved and should continue to do so.

Beyond the headlines about a high number of confirmed cases, there are a few positives to take away from the pandemic situation in India: case recoveries have notably increased over the past three months, while mortality rates have declined. This has brought the curve of active cases under control. Since July, these factors have combined to increase confidence among the government and the people to resume economic activity, even as cases continue to rise at a headline level.

Overall, despite rising infection numbers, we also sense that the COVID-19 situation is stabilising. Our base case does not foresee any further national lockdowns.

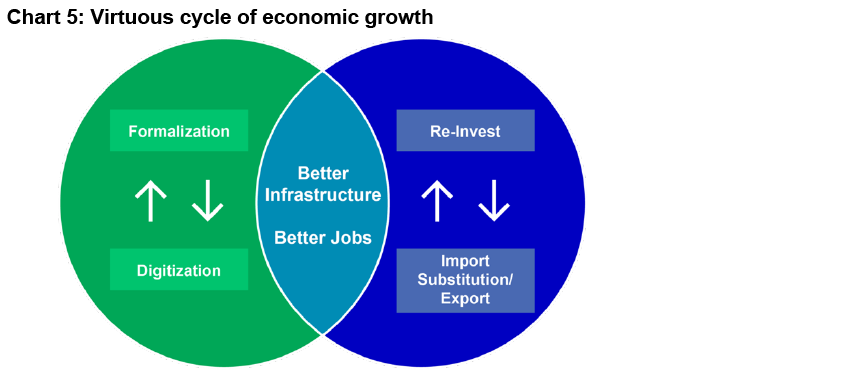

Over the short-to-medium term, we retain an optimistic cyclical view based on the gradual reopening of the economy. From a mid-to-long-term perspective, we are positive on the structural economic changes being driven by the powerful themes of formalisation through the digital economy and reinvestment in manufacturing. If anything, the pandemic has accelerated these trends; companies across sectors — from consumer staples, retail, healthcare, media, BFSI and even automobile companies have launched innovative digital platforms to engage with customers and find new ways to catalyse revenue growth. These developments have the potential to feed off each other and create the kind of virtuous cycle (see Chart 5) we’ve seen in China and other East Asian economies.

On the one hand, economic formalisation is driving the growth of India’s massive digital economy. In turn, the digital economy is itself propelling the formalisation process by boosting productivity.

We also believe that manufacturing growth is at an inflection point, led by the government’s supportive reinvest policies (incentives and tax cuts for domestic production) and a conducive global environment that is looking for a supply base outside of China. We have already seen a significant amount of investment by international firms, and this structural trend should continue to attract global capital to realise its potential8.

As formalisation grows, government revenues should increase, which, in turn, will lead to higher spending on infrastructure. As manufacturing expands, the creation of more formal jobs will drive income growth and consumption, thereby unleashing a virtuous cycle. Together, these themes will serve as strong drivers over the medium term, notwithstanding the recent cyclical challenges.

So far, the fiscal stimulus measures announced in response to the pandemic have primarily focused on liquidity (roughly 4.5% of GDP) and credit-guarantee measures (approximately 2% of GDP)9. There has been less of direct fiscal impulse (about 1% of GDP)9. Fiscal measures have avoided a broad-based fiscal impulse and focused instead on the provision of basic foodstuffs and income to the most vulnerable sections of society. It is possible that the government may announce additional fiscal measures when the economy is operating at a higher utilisation level to ensure they have a better multiplier impact.

More importantly, the government has concentrated its policy efforts on catalysing a longer-term manufacturing revival and increasing import substitution. These range from additional duties on imports, investment-linked incentives, as well as long-needed simplification of labour laws to improve the ease of doing business in India and incentivise more domestic manufacturing that are in line with the government’s reinvest policies10. Recently, the aim is to boost domestic manufacturing in sectors such as chemicals, active pharmaceutical ingredients (API), mobile phones, and consumer durables.

Such moves should lead to an increase in fresh investment leading to a recovery in the capital-formation cycle, improvements in employment opportunities, and gains in net exports for India.

Based on these changes in the Indian economy, we have updated our sector views:

More constructive on:

Less constructive on:

The key risk to our view remains a second wave of infections in India, pushing up the active-case growth curve and new lockdowns.

1 The Three R's are: "Recycle" (privatisation of state-owned enterprises), "Rebuild" (tax cut to corporates and middle-income household) and "Reinvest" (lower tax rate for investments on the ground).

2 The period from 1 April 2021 to 31 March 2022.

3 CEIC, Kotak Institutional Equities, as of 12 September 2020. The April 2020 data for ppassenger vehicle and two-wheeler were not released by the "Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers".

4 Manulife Investment Management made the GDP estimate. The other analysis comes from the Reserve Bank of India, 31 August 2020.

5 Reserve Bank of India and Bloomberg, as of 31 August 2020.

6 Bloomberg, as of 28 August 2020.

7 Bloomberg, as of 15 September 2020.

8 TIMESNOWNEWS.COM: "$20 billion and counting! Investments attracted by India in 3 months during Covid-19", 16 July 2020.

9 Manulife Investment Management estimates, as of 21 September 2020.

10 The Economic times: "Labour reforms intend to put India among top 10 nations in ease of doing business", 22 September 2020.

Middle East developments - Implications for Asian equities and fixed income

The Asian Equities and Asian Fixed Income team assess the recent Middle East developments and implications for Asia asset classes.

Quick comments on geopolitical tensions in the Middle East

Alex Grassino, Global Chief Economist, shares his latest views on the recent increase in military activity and geopolitical tensions in the Middle East.

Economic and market implications for oil prices

Recent geopolitical tensions involving Iran have renewed focus on oil prices and their potential economic and market effects. Paul Kalogirou, Head of Client Portfolio Management, Asia & Global Multi-Asset Solutions, shares latest views on it.